In the previous chapter, we used django.http.HttpResponse () to output “Hello World!” . This method mixes the data with the view, which does not conform to the MVC idea of Django.

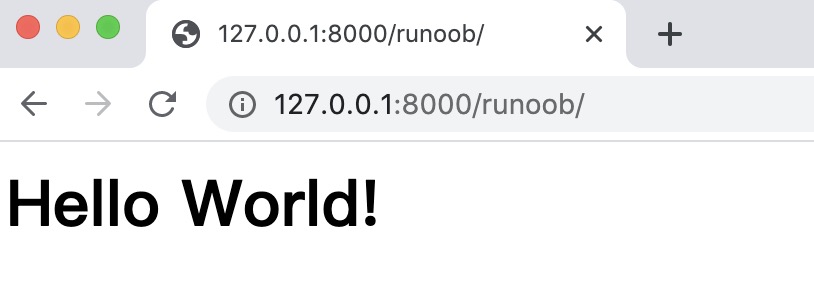

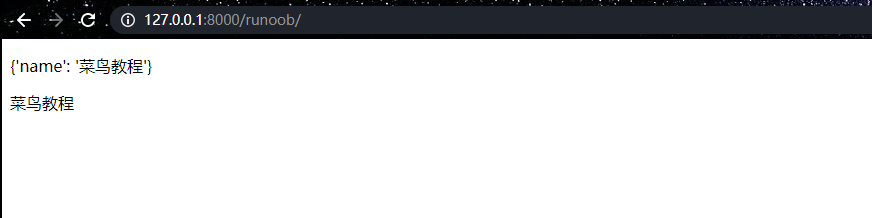

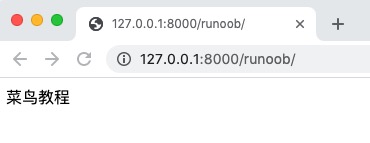

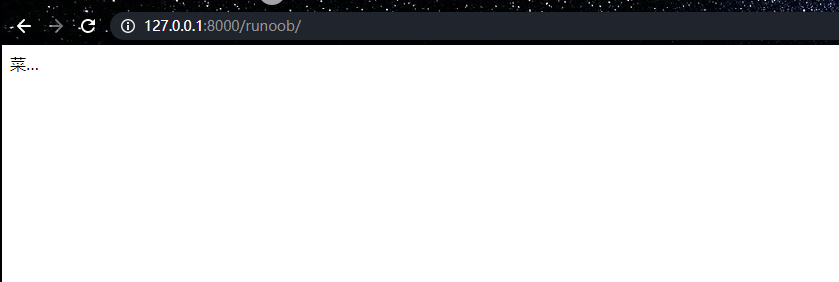

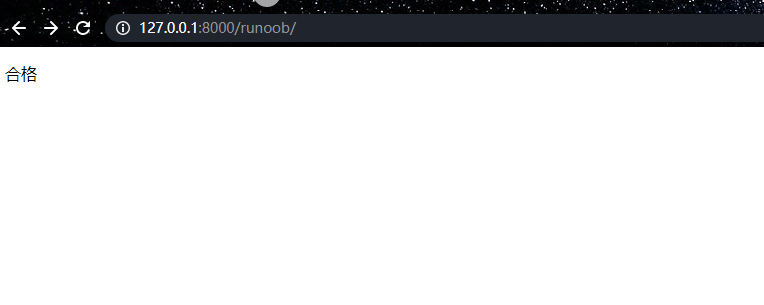

In this chapter, we will introduce in detail the application of the Django template, which is a text that separates the presentation and content of the document. The project we followed in the previous section will create a templates directory and a runoob.html file under the HelloWorld directory. The whole directory structure is as follows: The runoob.html file code is as follows: We know from the template that the variable uses double parentheses. Next, we need to explain the path of the template file to Django, modify HelloWorld/settings.py, and change the DIRS in TEMPLATES to [os.path.join(BASE_DIR, ‘templates’)] , as follows: We now modify the views.py to add a new object to submit data to the template: As you can see, we use render here to replace the previously used HttpResponse. Render also uses a dictionary, context, as a parameter. The key value of the element in the context dictionary hello Corresponds to the variable {hello} in the template. Visit again http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob You can see the page: In this way, we are finished using templates to output data, thus separating the data from the view. Next we will introduce in detail the syntax rules commonly used in templates. Template syntax: Runoob.html in templates: When you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: In runoob.html in templates, you can use. The index subscript fetches the corresponding element. When you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: In runoob.html in templates, you can use. Key to take out the corresponding value. When you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: Template syntax: The template filter can modify the variable before it is displayed, and the filter uses pipe characters, as follows: After the {{name}} variable is processed by the filter lower, the document uppercase converts the text to lowercase. Filter pipes can be* 套接* That is to say, the output of one filter pipe can also be used as input to the next pipe The above example takes the first element and converts it to uppercase. Some filters have parameters. The parameters of the filter are followed by colons and are always enclosed in double quotes. For example: This displays the first 30 words of the variable bio. Other filters: Addslashes: add a backslash to any backslash, single or double quotation marks. Date: format date or datetime objects according to the specified format string parameters. For example: Length: returns the length of the variable. default Default provides a default value for the variable. If the Boolean value of the variable passed by views is false, the specified default value is used. The following values are false: When you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: length Returns the length of the object, suitable for strings and lists. The dictionary returns the number of key-value pairs, and the collection returns the de-duplicated length. When you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: filesizeformat Displays the size of the file in a more readable way (i.e.’13 KB’, ‘4.1 MB’,’ 102 bytes’, etc.). The dictionary returns the number of key-value pairs, and the collection returns the de-duplicated length. When you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: date Formats a date variable according to the given format. Return in Y-m-d H:i:s format 年-月-日 小时:分钟:秒 Format time of the. When you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: truncatechars If the total number of characters contained in the string is more than the specified number of characters, the latter part is truncated. The truncated string will be truncated. The end. If you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: safe Mark the string as safe and do not need to escape. To ensure that the data transmitted by views.py is absolutely secure, you can only use safe. The mark_safe effect is the same as that of the backend views.py. Django automatically escapes the tag syntax passed by views.py to the HTML file, invalidating its semantics. Adding a safe filter tells Django that the data is safe, that it does not have to be escaped, and that the semantics of the data can take effect. If you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: The basic syntax format is as follows: Or: Judge whether to output or not according to the condition. If/else supports nesting. The {% if%} tag accepts and, or, or not keywords to judge multiple variables, or not variables, such as: If you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/runoob again, you can see the page: {% for%} allows us to iterate over a sequence. Similar to the case of Python’s for statement, the loop syntax is for X in Y, Y is the sequence to iterate over, and X is the variable name used in each particular loop. In each loop, the template system renders everything between {% for%} and {% endfor%}. For example, given an athlete list athlete_list variable, we can use the following code to display the list: 7.5.1. Template application example ¶

HelloWorld/

|-- HelloWorld

| |-- __init__.py

| |-- __init__.pyc

| |-- settings.py

| |-- settings.pyc

| |-- urls.py

| |-- urls.pyc

| |-- views.py

| |-- views.pyc

| |-- wsgi.py

| `-- wsgi.pyc

|-- manage.py

`-- templates

`-- runoob.html

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

<h1>{{ hello }}</h1>

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/settings.py file code: ¶

...

TEMPLATES = [

{

'BACKEND': 'django.template.backends.django.DjangoTemplates',

'DIRS': [os.path.join(BASE_DIR, 'templates')], # 修改位置

'APP_DIRS': True,

'OPTIONS': {

'context_processors': [

'django.template.context_processors.debug',

'django.template.context_processors.request',

'django.contrib.auth.context_processors.auth',

'django.contrib.messages.context_processors.messages',

],

},

},

]

...

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

fromdjango.shortcutsimportrenderdefrunoob(request):context=

{}context['hello']='Hello

World!'returnrender(request,'runoob.html',context)

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/urls.py file code: ¶

fromdjango.urlsimportpathfrom.importviewsurlpatterns=[path('runoob/',views.runoob),]

7.5.2. Django template label ¶

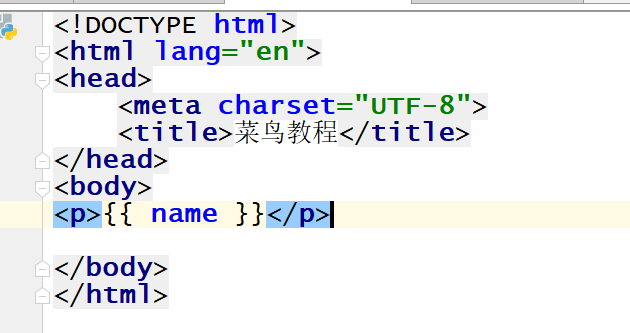

7.5.3. Variable ¶

view:{"HTML变量名" : "views变量名"}

HTML:{{变量名}}

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

views_name = "菜鸟教程"

return render(request,"runoob.html", {"name":views_name})

<p>{{ name }}</p>

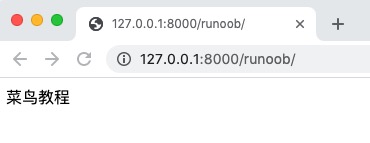

7.5.4. List ¶

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

views_list = ["菜鸟教程1","菜鸟教程2","菜鸟教程3"]

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"views_list": views_list})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

<p>{{ views_list }}</p># 取出整个列表<p>{{ views_list.0 }}</p>#

取出列表的第一个元素

7.5.5. Dictionaries ¶

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

views_dict = {"name":"菜鸟教程"}

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"views_dict": views_dict})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

<p>{{ views_dict }}</p><p>{{ views_dict.name }}</p>

7.5.6. Filter ¶

{{ 变量名 | 过滤器:可选参数 }}

{{ name|lower }}

{{ my_list|first|upper }}

{{ bio|truncatewords:"30" }}

{{ pub_date|date:"F j, Y" }}

0 0.0 False 0j "" [] () set() {} None

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

name =0

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"name": name})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

{{ name|default:"菜鸟教程666" }}

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

name ="菜鸟教程"

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"name": name})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

{{ name|length}}

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

num=1024

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"num": num})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

{{ num|filesizeformat}}

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

import datetime

now =datetime.datetime.now()

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"time": now})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

{{ time|date:"Y-m-d" }}

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

views_str = "菜鸟教程"

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"views_str": views_str})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

{{ views_str|truncatechars:2}}

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

views_str = "<a href='https://www.runoob.com/'>点击跳转</a>"

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"views_str": views_str})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

{{ views_str|safe }}

7.5.7. If/else tag ¶

{% if condition %}

... display

{% endif %}

{% if condition1 %}

... display 1

{% elif condition2 %}

... display 2

{% else %}

... display 3

{% endif %}

{% if athlete_list and coach_list %}

athletes 和 coaches 变量都是可用的。

{% endif %}

HelloWorld/HelloWorld/views.py file code: ¶

from django.shortcuts import render

def runoob(request):

views_num = 88

return render(request, "runoob.html", {"num": views_num})

HelloWorld/templates/runoob.html file code: ¶

{%ifnum>90andnum<=100%} 优秀 {%elifnum>60andnum<=90%} 合格 {%else%}

一边玩去~ {%endif%}

7.5.8. For tag ¶