For a wide-ranging research and project like NSDI, it is impossible to expect everyone to say it is a success. However, what is certain is that it serves as a catalyst that promotes development in many aspects (Longleyyet et al., 2005). As the “facade” of NSDI, the geographical information portal has played an important role. It simplifies information sharing, reduces duplicate data collection, and provides information support for many decisions. For example, during Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in the United States in 2005, the U.S. one-stop portal for geographical information quickly established a virtual community of hurricanes, publishing and organizing many key information, including data, map services and online map applications along the Gulf Coast. This information is used to assist federal, state and local agencies in emergency management and post-disaster reconstruction. In China, the Earth System Science Data Sharing Platform provides a large amount of data support for projects such as the design and construction of the Xizang railway, emergency rescue for the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, and environmental protection for the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

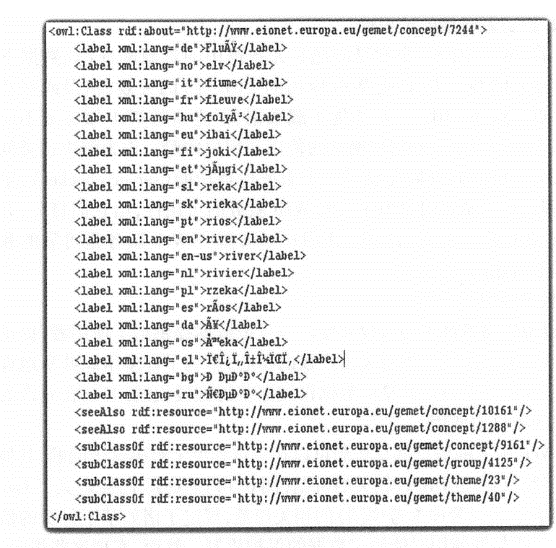

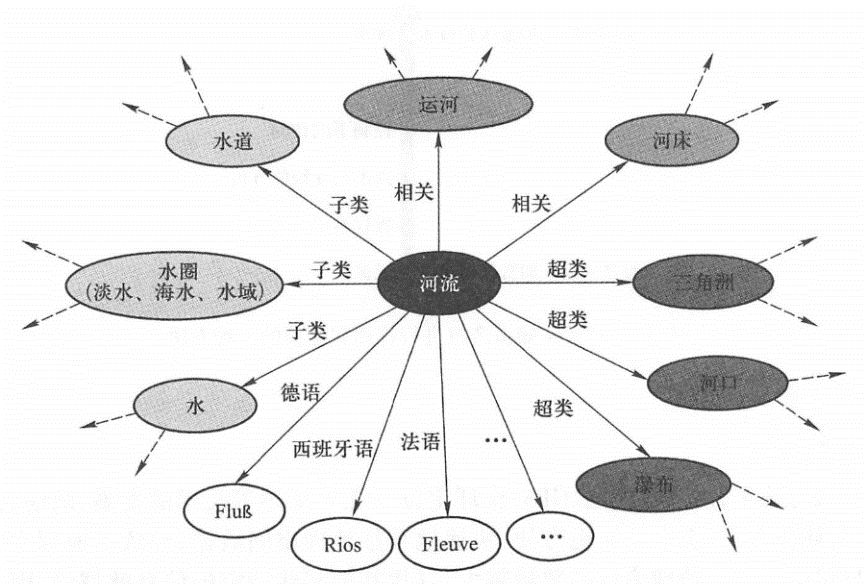

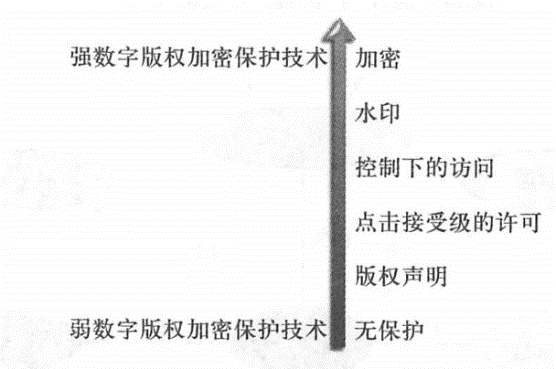

The further development of geographical information portals still has to address the challenges of excessive complexity of metadata, semantic search and information copyright protection. The complexity of metadata National and international metadata standards focus on comprehensiveness and inclusiveness, but often ignore simplicity and ease of use, which makes metadata specifications too complex and makes metadata itself a bottleneck in information sharing. We often hear: “Metadata is too complex” and “I don’t have the time or money to do metadata”. For publishers, the complexity and expense of creating lengthy metadata becomes a barrier to sharing data. Whether to use metadata standards is a difficult decision for many geographic information portal designers. This problem needs to be solved from multiple aspects. Standardization organizations need to consider developing simple standards; software vendors need to provide more convenient tools to automatically create standard metadata; geographical information portals can adopt “Metadata 2.0”, using tags, user comments, etc. instead of lengthy metadata, making it convenient for users to quickly publish information, and provide metadata modification functions, so that users who are willing to provide complete metadata or projects that require complete metadata can add more information. Integration with search engines Search engines such as Google, Baidu and other World Wide Web portals have a larger user base than geographical information portals, and when they need geographical information, most people’s instinct is to search in these large World Wide Web portals. Therefore, geographical information portals should be combined with these search engines to convert metadata into HTML, and let web crawlers such as search engines index these HTML, so that a wider user base can find the geographical information they need. semantic query Current geographical information portals generally cannot make full use of the meaning and context of keywords, and cannot solve the fuzziness of natural language. For example, when you search for “river”, you may also focus on layer information such as streams, canals, lakes, or other related hydrology, but this search mechanism that relies on spelling and string matching and lacks semantic support often misses the information you really need and leaves behind information you don’t want. The purpose of semantic query is to solve this problem. It is based on the meaning of the word, not just the spelling of the word. There have been some results in research on the direction of semantic query (Yang et al., 2008;Arpinar et al., 2006; Lutzet al. ,2004)。At present, the general solution is to adopt the Web Ontology Lan ® Guage (OWL) method. Ontology is a formal description of the conceptual system and the interrelationships between concepts within a category, and OWL is a description language of ontology. For example, the European Environmental Protection Agency took the lead in compiling GEMET(General Multilingual Environmental Thesaurus), whose OWL has more than 6000 terms and defines the interrelationships between these terms (Figure 6. 12)。OWL can also be described in charts (Figure 6.13). At present, semantic queries generally search OWL first to find terms related to the keywords entered by the user, such as synonyms and synonyms, and then use these words to query the geographical information portal directory, so that a more comprehensive search result can be obtained. Theoretically speaking, this method cannot be called a true semantic query. Semantic query is still the four important drivers of geographical information portal research. Fig. 79 Part of the European Environmental Protection Agency’s comprehensive multilingual environmental dictionary OWL that describes terms related to “river” # Fig. 80 OWL can also be described in charts. This figure shows the terms associated with “river” and their relationships in the comprehensive multilingual environmental dictionary OWL # (4)Availability of data resource links A common problem in geographical portals is the failure, error, or instability of resource URLs in metadata (such as the URL for data download, the URL for endpoint of Web services, or the URL for Web applications, etc.). When users click on these URLs, they will not be able to download data, preview Web services, or view websites, which greatly affects the use and user experience of these portals. As an attempt to solve this type of problem, the U.S. Geological Survey provides a server checker that regularly checks the availability of Web services registered in the U.S. one-stop portal for geographical information, scores them, and displays this score in user query results to let users understand which Web services are reliable and available and which are unreliable. copyright protection Digital resource providers are all concerned about copyright issues. Once the data is provided to the user, the provider loses control of the data. This fear of losing property rights has affected the enthusiasm of many organizations to share geographical information. They want the data they share to be used only by authorized users, within the allowed time, and in allowed projects. Web service-based information sharing mechanisms can solve this problem to some extent. Other methods include digital rights management (DRM)-related mechanisms (Figure 6. 14)。The OGC has defined relevant specifications for GeoDRM(Geospatial Digital Rights Management Reference Model), stipulating methods such as pay-based information protection and protection mechanisms that can lock data in case of illegal or extended use. However, implementing these regulations and fully integrating them into the workflow of the geographic information portal remains a challenge. Fig. 81 Multiple methods to manage and protect digital intellectual property # In recent years, due to the development of technologies such as the Internet, GPS (Global Positioning System), and remote sensing, governments, companies, scientific research institutions, and even individuals have been able to collect geospatial data more conveniently and quickly, resulting in a surge in the amount of geospatial information. The larger the amount of geographical information, the more difficult it will be to find some specific information, so the stronger the demand for geographical information portals. Compared with traditional data downloads, Web service-based sharing methods have advantages such as better timeliness (see Section 7.1.2). Therefore, geographical information portals should effectively support the registration, inquiry and use of Web services. In addition, geographic information portals are increasingly integrated with cloud GIS. Cloud GIS hosts numerous data and Web services, while geographic information portals can help users query information from cloud GIS. The two complement each other. Tim Bemers-Lee, the father of the World Wide Web, envisioned that the next generation of the World Wide Web should be the Semantic Web (see Section 10.2.2). In the Semantic Web, the semantics of information will be clearly defined for automatic processing by computers (Berners-Lee,Handler,and Lassila, 2001;W3C,2001). There is still a long way to go before the full implementation of the Semantic Web, but its implementation will reduce the fuzziness, uncertainty and inconsistency of natural language, and make the query of geographical information smarter and more accurate. Information sharing is not only a technical issue, but also a social issue. Information is power, and sharing it with the right partners will multiply the power of society as a whole. Due to national security considerations, some countries restrict the sharing of large-scale data. In fact, with the development of GPS technology, civilian GPS on the market, including GPS carried by general smartphones, can also reach an accuracy of 10 meters, which is higher than the accuracy required to make a 1:5000 map. There are also Google Earth and Microsoft Bing Maps that provide large-scale clear images of many parts of the world. Simply restricting the public use of geographical information data is of little significance, but instead limits the ability of GIS to serve society (Ye Jiaan, 2004). In addition, some data resource producers are unwilling or unwilling to actively share information for fear of losing control over the data. This requires the government to encourage information sharing in terms of policies, regulations, and funds (Onsrud, 1995). In 1966, then-President Johnson of the United States signed into effect the Freedom of Information Act. According to this act, relevant federal government departments have the responsibility and obligation to share government records and data that do not involve personal privacy or national security. Today, most countries in the world have formulated similar legislation and policies to disclose information and support SDI, which will provide a solid foundation for the research and development of future geographic information portals. In the future, smarter geographic information portals will support easier, faster and more accurate geospatial information resource sharing and more GIS applications.Challenges and research hotspots #

Outlook #