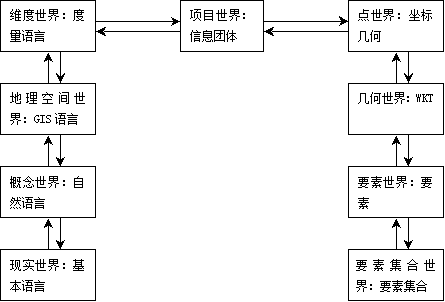

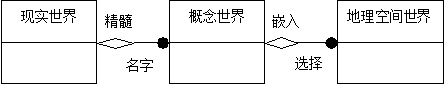

The abstraction process for geographic objects is commonly conceptualized through a nine-layer framework [OGC], interconnected by eight interfaces that collectively define a transformational model from the physical world to the realm of geographic feature collections. These nine progressive layers (as illustrated in Fig. 18 ) are structured as follows:

Real World

Conceptual World

Geospatial World

Dimensional World

Project World

Points World

Geometry World

Feature World

Feature Collection World

Fig. 18 OpenGIS Nine-Layer Model #

The eight interfaces connecting them are as follows:

Epistemic Interface,

GIS Discipline Interface,

Local Metric Interface,

Community Interface,

Spatial Reference Interface,

Geometry Structure Interface,

Feature Structure Interface

Project Structure Interface

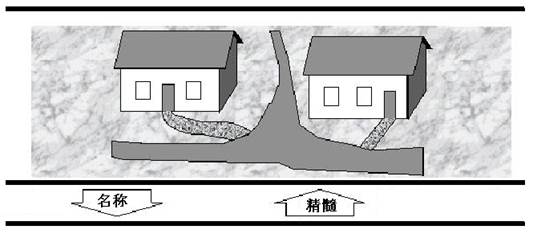

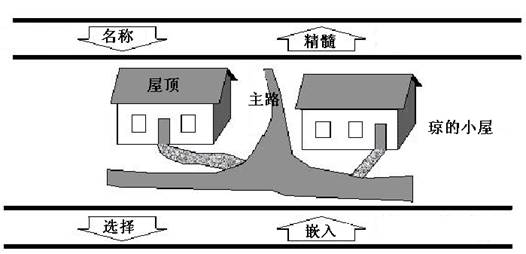

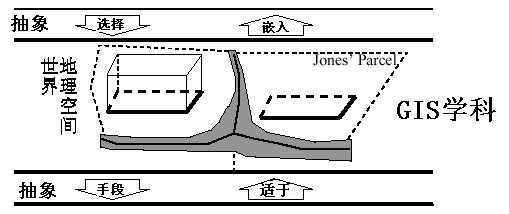

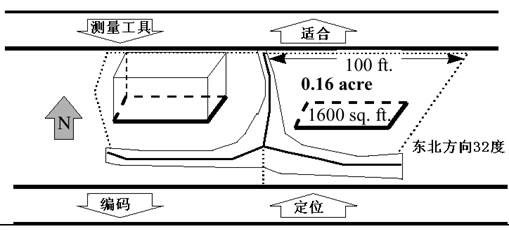

The first five models represent abstractions of the real world and are not implemented within computer software; the latter four constitute mathematical and symbolic representations of reality, destined for software implementation [ 1 ] . The real world constitutes the totality of all facts, regardless of human awareness. Through the essential nature of these facts, humans can comprehend entities in the physical realm. Fig. 19 depicts the reality in which humanity exists. Cloud-like textures dominate the illustration, representing unknown elements that contribute to the cosmos’ state of chaos. Human knowledge remains limited to familiar facts, with select examples visualized in the diagram. Fig. 19 Real world # The conceptual world represents the realm of human natural language, where humans understand and recognize named entities, thus forming a “linguistic universe.” In the conceptual world depicted in Fig. 20 , the chaotic cosmic clouds no longer exist, as such elements are typically unrepresented in natural language constructs. The schematic illustrates easily identifiable objects: doors, roads, bricks, roofs, houses, etc. Through this methodology, we can abstract the essence of facts from the real world, termed their “pith.” Since humans can assign names to known entities and perceive their fundamental nature, the interaction between the real world and the conceptual world is defined as the Epistemic Interface. Fig. 20 Conceptual world # For GIS, the conceptual world of natural language is not sufficiently abstract. Only a simplified subset of this conceptual world is of interest in GIS. This subset is termed the geospatial world, and the methodology for human interaction with the conceptual world is called selection. In Fig. 21 and the Geospatial World, there are three entity types. Each is represented by a rectangle and labeled with the name in its upper section. Fig. 21 Links between the Real World and the Geospatial World # The lines between rectangles represent relationships between entities, with each line featuring a role name at its endpoint to define the nature of the connection. The diamond symbol represents aggregation, indicating, for instance, that the existence of the conceptual world depends on the existence of the real world. The solid circle signifies the presence of a collection (rather than a single object) at that end of the relationship, indicating, for example, that each conceptual world embeds a series of distinct geospatial worlds. GIS professionals are accustomed to perceiving the world through an abstract, almost cartoon-like lens. This stems from the conceptual world’s inherent complexity, filled with intricate shapes, patterns, and details. Such complexities are eliminated in the geospatial world and replaced with simplified, explicit abstractions that are typically static in both temporal and spatial dimensions. Through this geospatial abstraction, rivers are reduced to lines, terrain is simplified into contour polygons, and forests are represented as polygons. The previously described conceptual world is reinterpreted at the geospatial level in a cartoon-like manner in Fig. 22 . While Fig. 22 is rendered in a perspective view, the geospatial world is typically observed from a “planimetric” vantage point, that is, vertically from above. Note how some features have disappeared from the diagram, while others have been significantly simplified. Fig. 22 Geospatial World # For instance, certain windows, walls, and building roofs have disappeared because they fall outside the scope of interest in the GIS worldview, they have become invisible to the GIS consciousness. Of course, there is no universal definition specifying exactly which features matter to GIS professionals; sometimes even a roof might be relevant. The cartoon simply illustrates that the geospatial world constitutes a simplified subset of the conceptual world, and the language spoken in this geospatial realm is that of the GIS discipline. In the diagram, building foundations remain visible even though they were partially obscured by other elements in the conceptual world. From a GIS perspective, all foundations of a structure are considered visible—even those physically hidden. Each GIS implementation follows specific rules governing which features are recognized in the geospatial world and how they are abstracted from the conceptual world. For example, one rule might reduce a brick building to a 3D polyhedron, while a house with different surface materials could be simplified to its foundation polygon. In essence, elements invisible in the conceptual world may become visible in the geospatial world due to their specialized interest in GIS. The interaction between the conceptual and geospatial worlds is termed the GIS Discipline Interface, with the methodological approach from the conceptual side called selection. To reverse this interaction from geospatial back to conceptual, we employ the embedding method, which positions GIS-relevant content within its proper context in the conceptual world. Features recognized in the geospatial world typically possess a natural dimensionality, 0, 1, 2, or 3, depending on whether they are represented as points, lines, areas, or volumes. Additionally, they carry further measures based on binary topological relationships such as containment, adjacency, or separation. The next level of abstraction identifies these inherent dimensional and metric properties of features, hence termed the Dimensional World, where feature measurements are acquired through instrumental observations in Euclidean space. The Dimensional world is an abstraction of geospatial world, including some measuring tools, such as tape measure and compass. The facts recognized at this level include the Unary relation (such as the length of an arc) and the Binary relation (such as the distance between two points), which are themselves abstractions of various elements. The interface between the dimensional world and the geospatial world is called Fit. The distance between the two telephone line poles belongs to the world of dimension. This length line is suitable for the length span seen in the geospatial world, and some of the abstractions represented in the dimension space are included in Figure 2-13. Fig. 23 Dimensional World # Dimensional world is the last abstraction of the real world. The next abstraction is called a project world, which only occurs in a specific implementation, each of which is aimed at a particular GIS discipline or sub-discipline. In each actual implementation, only one subset of the dimension world is identified. Usually this subset is determined by the scope of the study area and the specific phenomena to be measured. At the Project World level, the concept of a Spatial Reference System is introduced. The most common systems are coordinate systems established around the Earth’s surface (latitude and longitude); additionally, there are other indirect reference systems, such as linear referencing systems that can identify a point along a line (e.g., a highway) using a single parameter. Regardless of the coordinate reference system employed, it becomes possible to determine the coordinates of every “vertex” of features from the Dimensional World. The interface between the Dimensional World and the Project World is termed the Community Interface. Invoking this interface from the Dimensional World through a method called Codify results in the coordinates of each vertex being represented by a set of numerical values. Conversely, the method invoked from the Project World is called Locationing, which establishes the spatial relationships of each feature relative to others. There are two commonly used methods to model geospatial elements. The first model defines the spatial range of an element of points, lines and polygons, as well as a set of known primitive geometric elements, in which the element is called “Features with Geometry”. The second type is called Coverage. Image is a special example of this model. Geometric elements and coverage are closely related, but they are quite different in concept. The feature model is used to represent discrete objects in the real world, such as roads and cities, whereas the coverage model is designed to model continuous phenomena, including temperature and soil distribution. A feature possesses multiple attributes, such as spatial location, spatial relationships, descriptive characteristics, temporal data, and so forth. A coverage can also be regarded as an attribute of a feature. GIS is not just a discipline, It is also a language for the representation of geospatial information. The information comes from many disciplines related to geography, such as forest management, soil mapping, transportation model, cadastral management, etc. Each of these disciplines has many sub-disciplines, and a GIS project can contain any combination of these disciplines。 GIS is not merely a discipline; it also constitutes a language for representing geospatial information, which originates from numerous fields related to geography, such as forestry management, soil mapping, transportation modeling, cadastral administration, and so on. Each of these fields comprises multiple sub-disciplines, and a GIS project may incorporate any combination of them. A geospatial community refers to a user group that shares data, comprising members from diverse professional backgrounds who may act as either data consumers or data providers. This community perceives a specific subset of the entire geospatial world as an abstraction. In three distinct applications, the aforementioned example is abstracted into three different Project World models. These are illustrated in Figure 2-14, reflecting the Project Worlds from the perspectives of a cartographer, a cadastral administrator, and a road manager, respectively. Fig. 24 Project World # Real world #

Conceptual world #

Geospatial World #

Dimensionality World #

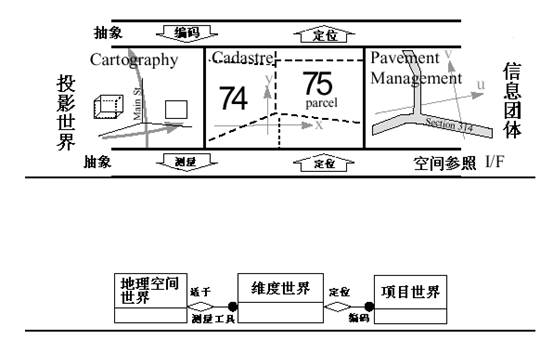

Project World #